“They’ll stick to you like glue,” my mother had chuckled. Hordes of relatives. Like lice from boarding school. “They’ll all come back with you”.

As it happened, only a single relative came. One Fourteenth Aunt. I arrived in good time at the San Francisco Airport to pick up my mother’s fourteenth sister from Beijing. However, as I stood waiting, my mind preoccupied with editing the footage from my recent assignment in China, I was struck by a sudden, and completely inexplicable, lapse of memory. I could not recall what Fourteenth Aunt actually looked like.

Repeated searches produced nothing more than a stubborn blank where her face should have been. Well, she was not a person who stood out… Lame! I reached for excuses. She was a kind of a practitioner of anonymity. I laid it on her. It was how she had survived the wars, the revolutions, the purges…None of my rationalizations resulted in a usable image. I faced the prospect of a gigantic gaffe.

In the crowd due to pour out of the double doors of US Customs she would be as invisible as she had become in my mind. I backed away to position myself in the rear of the hall between some guys holding name cards. Perhaps my memory would snap into focus upon her actual arrival.

Perhaps not…

Only a few months had passed since I‘d seen Fourteenth Aunt. She’d had an important part in the success of my assignment in Beijing. Early in 1985 I was in the rear of a wave of American journalists sent to China to report on the “failed” revolution. Network anchors were seen on the evening news, standing on the Great Wall or in front of the Forbidden Palace trumpeting the much-heralded turn away from “hard line isolationism.” At that time I’d been making Public Affairs documentaries on local issues for the San Francisco ABC affiliate for a couple of years. Though I’d been in the states since I was twelve, I still spoke some Chinese, and managed to convince my bosses that I could get a foot in Deng Xiaoping’s “open door”.

This was a big plum of an assignment. I was very fired up to be going back to Beijing where I was born, and where I had spent a happy childhood. And how glorious that I should return as a journalist with a film crew bearing camera gear in sleek but authentically weathered aluminum cases slathered with glossy stickers of ABC-TV.

The start of the project, however, was as inauspicious as it could get. Phone communications with Beijing were nightmarish. The time difference of 15 hours, the clogged circuits, the intermittent connections, my awkward, kindergarten Mandarin, their bureaucratic lingo….

The hope that things would get better once I was there was dashed as it got even worse. The first couple of weeks were spent mostly dead-ended in one or another of Beijing’s wretched vestibules—tiny, smelly, unheated, waiting rooms wall to filthy wall with eternally unsuccessful petitioners. Their despair was catching. Beijing was rejecting me.

[/full_width]

When we were still in San Francisco, Comrade X of the Ministry of Propaganda had called me from Beijing to offer his help but I was leery of getting too tight with the government. Last thing I wanted was a censorious presence to hinder my shoots and interviews. Upon my arrival, he called again with an offer to throw a banquet for both sides of my family. Everyone was delighted to accept. I had no excuse to decline.

When I actually met him for the first time the night of the banquet, I was quite charmed by him. He was not the bureaucrat I had expected. He was an old revolutionary who had been on the Long March who wore his weathered Mao hat with a jaunty tilt. It was he who had unearthed Tiger Aunt’s widowed husband, and through him Number Fourteen.

Fifth Aunt

Comrade X at the Welcome Banquet

Fourteenth Aunt began to call me every morning, before it was light, before the phones lines were overloaded, while I was still in bed at the very posh, very American Great Wall Hotel with whom we had traded credits at the end of our forthcoming program for complimentary rooms. In her calm and measured voice Fourteenth would ask what our tasks were on that day.

An old hand and once a middle school principal, Fourteenth Aunt guided me through the Beijing maze. This one had been my father’s student; that one had been Fifth Aunt’s neighbor

It was as if finally Beijing began to recognize me. We taped a nostalgic episode with Cousin Mingzhen taking me back to the house where I had grown up. Comrade X arranged for us to shoot at The Forbidden City, the Imperial Palace, the center of the earth, when it was closed to tourists. The night before, it snowed; they said it had not snowed in Beijing for many years. It was, literally, icing on the cake.

People on the street allowed us into their lives. They talked on camera with a comfort that I didn’t expect. We got more stuff than we needed. I was exhilarated and scratched a previously planned episode on Beijing’s unsuccessful petitioners.

On the day we were packing to leave, Fourteenth had come, once more, to the Great Wall Hotel, an exact replica of the Hilton in Houston, a monument in smoky glass rising from the yellow dust of Beijing. She was loaded with bags and boxes of carefully wrapped knickknacks for me to take to my children, my mother, my brother, his wife, his daughter,

Cousin Mingzhen and Fourteenth Aunt at the dinner

Our Crew at the Imperial Palace

Not wanting to seem ungrateful, I apologized as profusely as my limited Chinese allowed. Deb said to offer my aunt a job as production assistant in San Francisco.

Up in my room Fourteenth sat down, and watched, passively, the flurry of packing that surrounded her. Then her hands shuffled through her packages, now spread on my unmade bed, dispiritedly at first but then with increasing determination, looking for something small enough to fit inside something else, not taking up any additional room, something as unobtrusive as Fourteenth herself. Finally, I allowed, with as much grace as I could muster, a silk scarf and a little bag of tea to be stuffed inside a pair of high heels.

“Come to America, Fourteenth Aunt,” I said as compensation for my rude intransigence. “Come and bring these gifts yourself. My mother is all alone, and too old to travel. Come and visit her. She’d love to see you.”

Few Chinese made it out the government’s officially declared “open door” in the early eighties. Those that did were a select group of luminaries—ministers, bureau chiefs, deans, ping-pong champs, and the like. It was hard to place Fourteenth among them. She had been a middle school teacher before being transferred to some kind of travel bureau work.

At the time I was committing my mother to love, I never thought it would come to the . In truth, my mother had told me once that she spent her life avoiding relatives. Sisters, brothers, her father, his concubines, dead or alive, she’d never had a good word for any of them.

They began to come through Customs, the colorful crowd of arrivals, unmistakably from The Peoples’ Republic of China with big leather suitcases, bundles wrapped up in wild floral prints, women with their opaque stockings rolled below their knees, calling loudly, beckoning, greeting with such energy and enthusiasm you’d never know they had been flying for sixteen hours. They were so fresh, so ingenuous, these denizens of the Central Kingdom newly released upon American soil.

When I spotted her, Fourteenth was already out of the double doors, and standing next to a portly man wearing a Mao jacket, bidding him good-bye. Memory miraculously revived, I pushed through the crowd. My hands went out and caught hers. “Fourteenth Aunt! Your hair is curled!” For a moment I visualized her back in Beijing with her head in a roaring helmet of hot air at the White Beauty Salon, where we had taped a sequence on the new “western” look.

CITS, Fourteenth explained, had arranged for CAAC to fly her without charge, and she didn’t have to be back in the PRC for three months. Another major bureaucratic coup!

It was necessary for me to drive her to my mother’s immediately as this was my one day off from editing. She lived in Mendocino, some one hundred and fifty miles north of San Francisco. So after sixteen hours of being in the tail of a flying machine Fourteenth got ready for more movement by swallowing, without water, another tablet for motion sickness from a riddled card with two rows of freshly shattered holes. A tiny glass vial of silver seeds, however, she looked at but returned to her flight bag. “Ai! No need for this anymore. This is for calamities.”

I aimed the Volvo toward the Golden Gate Bridge, and Fourteenth leaned back into the seat as if she expected us to take off. “What if I missed you at the airport? Were you worried?” I asked her.

“Not at all! I learned some English. Well, just one sentence in case they ask me what am I doing in America: I beeseetuh my seesssterrr. We laughed, and her life was without difficulty for four hours as she slept.

There really were hordes of relatives. In my mother’s family there had been twenty-one children not counting ones dead too young to be numbered. Her father had had two consecutive wives who were sisters and four or five, or maybe even six concubines. “A sex maniac,” was how Number Two, my mother, once described him.

Only a handful of the twenty-one had survived first TB, then the Japanese invasion, followed by the revolution. Among them was Number Fourteen whom Number Two did not remember; she had already left home when the younger one was born. Anyway there were so many.

Fourteenth, however, remembered Second Sister. Over eighty now, Second Sister was the oldest living member of the family. Always remote and even formidable, she had moved to America forty years ago. After it had become permissible to write to relatives in capitalist countries, Fourteenth had written polite, who’s where and doing what letters folded around small black and white uncommunicative i.d. photos.

When my mother read them to me, I had listened with intense attention. While I was growing up, Fourteenth had been bedridden with TB and quarantined from me by my health conscious mother. Many of those Fourteenth mentioned, however: Twelfth Uncle, Fifth Aunt, Sixteenth Uncle had very special places in my childhood memories.

My mother lived alone in the deep woods of Mendocino at the end of a dirt, and gravel road in a house she had designed herself. When the dust of our arrival had settled, she came out of the sliding glass door, and turned on her hearing aid as she approached. She squinted at the stranger getting out of my car and let forth a sinking, “I don’t remember you.”

“Second Sister,” Fourteenth called her as she stepped onto the weedy driveway, then stood, arms dangling, waiting for recognition.

“I don’t remember you,” my mother repeated, warily circling and inspecting.

Fourteenth sighed, “Ai,” and smiled a rueful smile. “Don’t remember me.”

Oh, please let my mother rise to the occasion! I ran about making a great commotion, commenting on the foggy weather, putting water on for tea, dragging Fourteenth Aunt into the house, dragging her enormous suitcase after her.

Several extra nylon straps secured the suitcase. When we finally had it opened on the floor, I saw that the knickknacks I had rejected had mated and multiplied. On her knees she dug around well-wrapped packets and boxes, and pulled out a large envelope. “I brought this for you,” she said to my mother, approaching on her knees, and presenting it with both hands.

My Mother, Her Siblings, Their Grandfather

It was an extraordinarily well-preserved old sepia tone print of a group portrait taken on a verandah. An elegant old man with a wispy white beard was seated, legs crossed, holding inhislap a chubby baby with a cap topped by a pom pom. Surrounding the seated old man were eight kids, standing or sitting on the steps. On the right, standing, gazing petulantly into the camera from the long distant past, legs planted defiantly apart, an adolescent beauty in padded pedal pushers, high collared vest, a delicate wrist bone showing below the 3/4 length sleeve, was my mother.

Most of a lifetime later, she got out her magnifier and bent over the picture and with Fourteenth’s help made out her brothers and sisters. But which one was Fourteenth? “Are you in here?”

She was at the center of the photo, the fat baby in the grandfather’s lap. She had brought the photo to validate her position, to identify herself to my mother. “I still don’t recognize you,” said my mother, the immutable.

“But you know me now, don’t you?” Perseverance, thy number is fourteen. Second Sister laughed.

Later they were drinking tea. My mother was introducing her big white Samoyed to Fourteenth. “My big fear is,” I overheard my mother saying. “Dying alone and then being eaten by Boris.”

When I drove away that evening, I could see the two sisters, two little old widows about the same size and shape, one with straight white hair, the other’s black, curled, standing together, framed by the glass walls of my mother’s six sided redwood modern, lit like an amber Chinese lantern in the vast night of Mendocino.

A couple of weeks went by before I heard from Fourteenth Aunt again. She phoned me one early morning just as she used to do in Beijing before the lines were all clogged. “Yeh Tung” she called me. By not using the diminutive “Ah Tung” which is what all older relatives call me, she stressed camaraderie and equality over the generation gap. “Yeh Tung, what am I to do? Your mother’s dog knows more English than I do!” I laughed and invited her to come down to the city to stay with me for a while. Postproduction was finished.

She rode “The Gray Dog”, befriended by two hippies who showed her how to change buses in Santa Rosa. When I picked her up, she was inviting them to visit her in Beijing. English or no English, Fourteenth knew her way around.During her stay with me a slight smell of peppermint pervaded my house from a little bottle of clear oil in her flight bag. And I enjoyed, for the first time, the luxury of having my supper ready for me when I came home from work. It was marvelous to have an aunt.

Besides spoiling me, she instigated reform in my kitchen, reform that, I realized I would have resisted fiercely had it come from my mother. My dog was not to lick the dishes for sanitary reasons. Chicken necks were not to be thrown out; they were the tenderest part. The outer stalks of celery could be eaten by stripping the tough rib fibers. The first water used to rinse the wok could be made into passable soup. It was strange enough that we in America all liked to live alone with our dogs, but waste was profoundly out of order and counter revolutionary to the extreme.

The slurp she made drinking soup moved me. I was reminded of the way my mother ate, a creature in a private biological act of survival.

In Beijing I had visited the apartment where Fourteenth lived with her son, his wife, and their one adored daughter, but beyond that I didn’t know much about her. “Fourteenth Aunt, how did you become a revolutionary?”

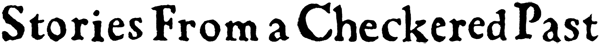

“Third Brother. San Jio, Third Uncle is what you would call him if he had lived.” Wiping her wet hands, she walked from the sink across the kitchen over to my bulletin board and removed the copy I had made of the family portrait. She pointed to the young man who flanked the grandfather on the right while my mother posed on the left. He stared back at me with profound silence. He looked to be about thirteen.

Third Uncle

“Third Brother was in love with a little indentured maid who worked in our kitchen. Now it was quite all right for a young gentleman to carry on with maids; it was the usual thing, you know. But Old Number Three was serious. He asked her to marry him.” She smiled her rueful smile. “When Baba, your grandfather, heard about it, he exploded. ‘A kitchen girl! A chicken plucker, the mistress of the Yuan clan! Dreaming!’ The maid disappeared. Probably sent back to her native village. By week’s end Number Three was also gone. A runaway. Nobody knew where. Months later a letter came for his stepmother from Shanxi province. His stepmother was also his aunt since our father married his wife’s sister when the first passed on. Did you know that?” I did know that but not much more. “She cared for him and for your mother as much as she cared for her own kids. He wrote that he was going to school by day and working as a waiter at night to support himself. Don’t worry about him. He was fine. He shared living quarters with comrades of the Communist Party. Please send his winter quilted jacket and some medicine for coughing.

The Communist Party! Your Grandmother went crazy. She raved that Number Three was possessed by the Fox Spirit. She went out of her mind and wasn’t right for months after that. “The Fox Spirit!” Fourteenth Aunt chuckled, and shook her head. “That was just how ignorant our people were. By that time,” she counted on her fingers. “1921, 1922…late 1920’s anyway, the Russian Revolution was already a fact of history, but the Yuans were still talking about the Fox Spirit!”

“What happened then to Third Uncle?” My mother had never mentioned any of this; the Russian Revolution, the Chinese Revolution, Third Uncle’s conversion, The Fox Spirit had all seemed equally irrelevant to her. She elevated isolationism to an art form, and I grew up deficient in family history.

“When Third Uncle came back to Beijing, he was already very ill with TB. Even then he wasn’t allowed home. Baba forbid the mention of his name. The strange thing was Baba himself was dying. They died, one after the other, a couple of days apart, Third Uncle in a little unheated room tended to only by an old servant. Before he died we, all the younger ones, all went to see him, and he gave us his diary. He wrote with deep feeling, and in the diary there were very moving poems about the suffering of the poor, and his romantic feelings for the maid.”

“Where is it now the diary?” I imagined an old tattered volume smudged with ink, hand sewn, a treasured record of Third Uncle’s idealistic passions.

“Oh, it’s long gone. So much has happened since. But that diary…You see after that more of us got TB: Eighth, Tenth, Twelfth, me, Sixteenth.

We spent months in bed with nothing to do but read the diary over and over again, and we got all the pamphlets and books that were mentioned in the diary. Twelfth Uncle gave them to me and I passed them on to Sixteenth. Communism and TB spread together. That’s how we all became revolutionaries.”

That’s how we all became revolutionaries. Viva La Fourteenth! In my Cost Plus kitchen the old revolutionary got another stalk of celery, cracked it in half, and peeled the rib fibers from its back. “Enough for tonight”, she stretched and eyed her bed on my back porch. But I was not ready to let her crawl into her nightly cocoon of meticulously folded quilts.

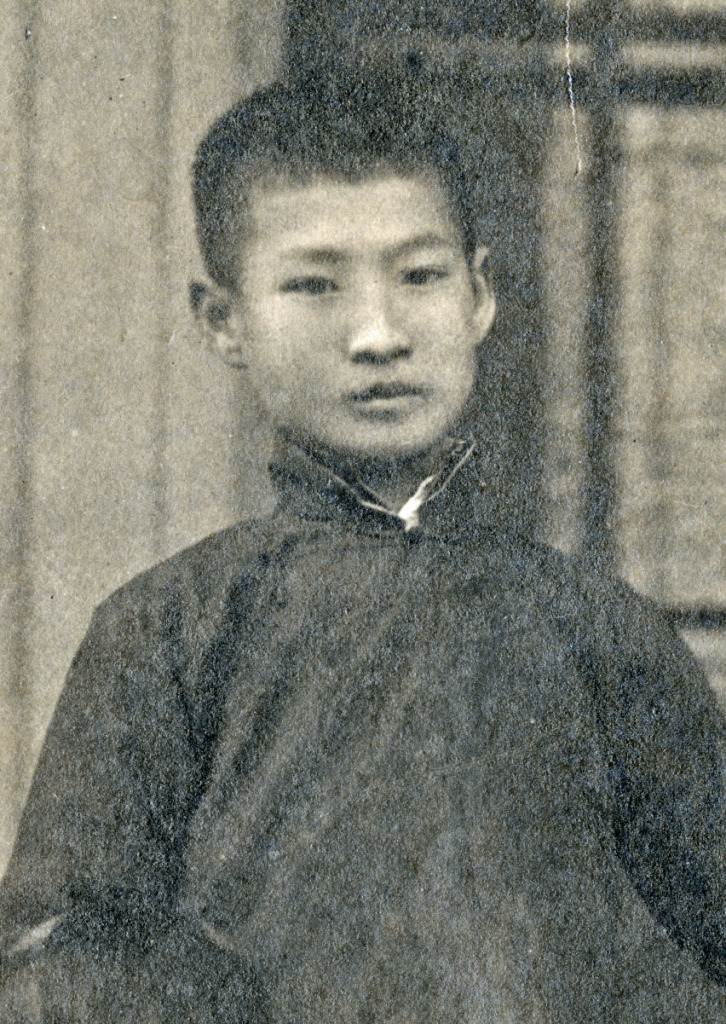

Twelfth

Tenth & Eighth

Although she was already taking out her teeth which made her lips sink into her jaws and which usually made me giggle, I was not to be distracted. I begged her for more. What did she do in the revolution? What were her adventures?

She chuckled. “You want more stories, eh?” She put back her teeth and went to get the green sweater she had been knitting for my mother. I turned on the gas under the kettle and poured peanuts into a bowl. “Mostly I did printing.”

In 1948 the old guard, the Kuomintang Party (KMT) had yet to be toppled. Fourteenth, Eleventh, Twelfth, and Sixteenth were living in Cotton Alley where the family had moved after Baba had died leaving nothing but gambling debts. From the east room of the rear courtyard that was the former dining room, they operated an underground press. There was more.

“I had a girl friend in college. We shared lectured notes, and bus passes, and hairpins and so on. She always liked to busy herself on my account. She felt sorry for me. I think, because I was skinny, and small, and not well dressed. She was considered a beauty and very popular.” I could see the pair: a bubbly hi flyer and runty, quiet, pockmarked Fourteenth.

“Anyway after graduation she married an up and coming KMT officer. I ran into her in Dried Noodle Hutung one day. She said to me, ‘My husband has so many connections. Why don’t you let him get you a job? You can’t live off your sisters forever. I’ll ask him tonight.’” Her head wagged as she mimicked the friend’s high-pitched rapid speech. “I didn’t answer yes or no, but soon I was offered a job in the accounting department of the KMT army. I asked the party cadre what I should do. They said, ‘Take the job’”.

So mousy little Fourteenth, splendidly attired in her new olive green uniform with red epaulettes (her friend was ever so proud of her) rode her bicycle to work without incident for several months.

Then one day all the workers in their department had to have their pictures taken individually, and then once again as a group. Some said there was a leak in accounting. There followed the first interrogation. It seemed routine; she was not too worried. After all everyone in the department was interrogated.

Then there was a second interrogation in which she and two others were called out of turn. At that, the printing press in the dining room was quickly dismantled and under the cover of night moved out of Cotton Alley. The cadre was now under the leadership of The Monkey, a famous guerrilla fighter, and Fifth Aunt’s husband’s little brother. They’re trying to flush you out, he told her. Keep going to work. Adhere strictly to routine. Do not pass us any more information. Other than that, change not even the part in your hair. She was surprised he noticed her hair.

One night as she pulled her bicycle out of the rack to go home after work, she felt a gloved hand on her shoulder. It was the interrogating officer. He’d like to have another little chat with her; since it was so late, would she come to his home on the West side of town? She rode her bike while he drove his car behind her. Was it still too early for her to run, or was it too late?

His parlor would be quite formal, smaller but not unlike the hall where we had taped an interview with the Vice Foreign Minister, with antimacassars on the backs of stuffed chairs. His wife would be likewise antimacassared with a little lacy collar. They were both extremely cordial, plying her with tea and sweets and complicity. He knew that all the youths of today read left wing books; he didn’t care; he’d read them himself.

Someone had turned her in, he said. She denied everything. Perhaps someone had a grudge against her? Well, there was a fellow in Shipping who’d asked her out several times and she’d refused. What about a man they called ‘The Monkey’? Know him? She didn’t recognize the name. She didn’t know him, and she knew nothing about him.

Across town a small lean simian figure, a Chinese Claude Rains, cigarette dangling, hat cocked, hands in pockets, strolled nonchalantly out of Cotton Alley.

Meanwhile the interrogator was finished with her. He and his wife were going out to supper and would drop her off at her house. She thanked him and declined because she needed her bike for work tomorrow. He said not to worry about work tomorrow. Her situation was clear then. She had him drop her at the Public Baths where in the half dark clouds of steam she disappeared.

“I didn’t go back to Cotton Alley again for a long time, not until we came back to Beijing with the People’s Liberation Army.” She hid at several comrade’s homes for a couple of months while posters of her unsmiling, uncommunicative face with thick glasses went up around town and at the guard houses at the city gates.

One morning a young couple knocked on the door—makeup and costume artists of the People’s Drama Troupe. They cheerfully transformed Fourteenth into a blushing bride: her hair brilliantined and bangs cut, her glasses removed, her face powdered white, cheeks rouged pink, eyes outlined. A bright red satin outfit, with pink stockings and embroidered red shoes completed her disguise.

They placed a three-tiered lacquered tray of wedding sweets in her lap before they secured the flaps of her covered rickshaw. At the city gate the guard lifted up the flap. He smirked and said, “May you bear many sons!” The flap dropped down. Her anonymous features had served her well. A couple of li’s away from the city by a vegetable peddler on the side of the road, she stepped out of the rickshaw. Among the cabbages and turnips were her glasses. The peddler pointed the way west, and wished her luck. On foot she headed for red territory upon little dirt paths bordering fields of green and yellow.

“Oh I felt great then!” She broke into a smile remembering. “It was a lovely day, bright, clear, and not even very cold. I hadn’t gone far before my belly started to rumble. I sat down on a mound of dirt and opened up that box of wedding sweets and ate them. The swee sweets I ever ate! Then a man approached, and seeing me, broke into loud laughter. He was another comrade going west. He said the peddler had told him to look for a bride on the way!”

“What a story!” I said.

“And there’s more,” she said as if all that had been prologue.

“More! Let me guess! That man was The Monkey? You married him and the two of you went off into the sunset and lived happily ever after in an egalitarian socialist society.”

“No, no, no. Well, later, I did marry The Monkey, but that was much later. That woman,” she continued in a more serious tone, as if only now was she coming to the point of her story. “That schoolmate who married the KMT officer who gave me the job in the army, that woman lives in New York now.”

Ah. The friend. I had forgotten about her. Fourteenth had deceived her, had used her well-meaning gesture to further The Cause. What happened to her? What happened to her husband after Fourteenth escaped? Did he pay for placing a spy in army accounting? What was the price of Fourteenth’s glory?

“Actually not much happened to him. He was promoted just the same. Later they both went to Taiwan and he became a big brass before dying quite a few years ago. She moved to this country with their two children. Now they’re grown and she lives alone.”

Fourteenth had written the woman about her impending trip. The friend had answered, and had asked her to visit. While at my mother’s Fourteenth had called. What did the woman say?

“She asked me ‘What do you have to say for yourself?’ I said ‘Sorry.’“

“You said ‘Sorry’ in English?” I was amazed.

“Eh,” she nodded.

I pictured her with my mother’s Princess phone to her ear, bobbing her head of curls, and saying “Sorry.”

“And what was her answer?”

“She said ‘Sorry! Just sorry? After all you’ve done? Just sorry? That’s not enough!’“ Her head wagged again as she mimicked the woman’s manner of speech. Then Fourteenth made sort of an uneasy laugh. What could she do? What was done was done. Then Fourteenth told her she was going to visit relatives in Los Angeles and Baltimore and from there she could perhaps come to the suburb of New York where the woman lived.

This time Fourteenth Aunt traveled with $300 in travelers’ checks given to her by my mother, and from me a little cassette recorder with a tape of useful phrases I had recorded, and she had practiced: Where is the restroom? I’m going to Los Angeles on flight 84 American Airlines…Get away from me; I’m calling the cops!

When she returned to San Francisco, her big suitcase was well on its way to being filled again with packages and boxes she was taking back to China for this one and that. Resettled in my kitchen, she said Disneyland had been fun. But New York? “Hmmph!” she snorted. “What New York? The woman works. She didn’t want me to get lost in New York, so she locked me up in her apartment!” She shook her head, chuckling. I imagined the other woman, face a mask of pancake makeup, turning the key from outside the door, and Fourteenth inside an apartment where the armchairs wore antimacassars. The woman had waited almost forty years to lock the little Bolshevik spy in jail. “So I only stayed two days, one night and went back to Baltimore. Two days were enough! I got enough of a look at her life. Can you believe that at her age, 63, she is still running after men? And with her looks! She is ugly now. Her eyebrows are shaven; she draws them in with a pencil. Her boss, she’s sure, is after her. After what? I ask you. Dreaming! Ugly and old and fat she is now. He has never ever so much as spoken two words to her! Just the way he looks at her, she says. Ha! She’s a sanitation worker at a school. He just looks at her! She looks at him! Her with her pink rubber gloves, smelly disinfectants, brooms, and mops, and toilet brushes. The major problem in her life is how to get him to talk to her, then from there to marry her. An earth-shaking problem! Calling for a ten year plan of seduction! Imagine, a woman of 63!”

Tssssslaaaa! She threw vegetables into the wok and when the sound died down, she too took a softer turn. “Actually I feel sorry for her. Her life is sad, living all alone in a little apartment, and working as a toilet scrubber at her age, and she has no retirement, so she just has to keep on working until she dies. And her son! She has to pay him to come and fix her car or work on her house. Her own son, a grown man! We’ve heard that’s the way things are in capitalist America. Money is everything. Now I’ve seen it.” I assured her that not all Americans are like that. “And she thinks my life is pathetic! Oh, we got into such arguments because she is overflowing with Taiwan propaganda. She thinks we on the mainland are so backward and so impoverished. Truth is we have everything we need. You have been there; you have seen. I may not have a car like she does, but I don’t need one, or the toaster, or the washer/dryer. I told her to come visit and see for herself, but she won’t. Look at this old beat up sweater she gave me. I was never so insulted! It even smells!” She was wearing a sweater that was indeed undistinguished, a generic gray nylon sweater, badly pilled. “Do I need her castoffs?”

Why had she taken it? She sighed, “Ai, to give her face! I did refuse at first, but she kept trying to give me things. She kept insisting. Oh, you know, I’ve come all this way, and we have all that business behind us, the least I could do was to give her some face. Let her think she’s helping me out.”

“I’ll dump it for you,” I thought perhaps she felt somehow too obligated to throw it away herself.

She poured herself a bowl of rinse water soup from the wok. Then she pulled and tugged on the old sweater to examine it. “Well, its still got some wear in it.” Smell and all, she wore it and continued to wear it quite often.

She began now to prepare for her return to China. She would go once more to see my mother and keep her company for about a month. We never talked about my mother. As she never mentioned her second sister without a tone of extreme reverence, I kept my convoluted and subversive feelings discreetly underground. My only clue as to how she really perceived my mother was the sweater she knitted for her. Although Fourteenth is a superb knitter, the sweater for Second Sister came out ugly, the knit too thick and tight, and the whole thing altogether too small. My mother looked cramped in it.

Before Fourteenth went up there she asked if my mother had talked about her, she wondered if my mother had found her to be a nuisance. What could I do but lie?

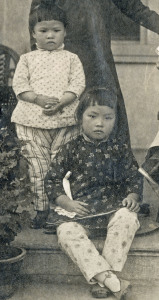

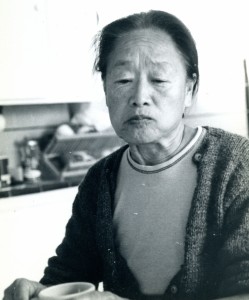

My Mother as a Teenager

My mother trashes everyone and Fourteenth was no exception. My mother complained that after so many weeks Fourteenth still never learned to use the paring knife on its right edge, that she used too much sugar in her cooking, that she never allowed my mother to do anything, waited on her as if she were an invalid, helped her too much, even grabbed her letters from her hand to read them to her, well she may be hard of hearing but she was not blind, in fact she was generally in far better shape than her younger sister, she walked much farther without getting tired, worked longer periods at cutting wood, Fourteenth maybe younger but she was no match for Second, she had more than a few things to learn from her older sister. There’s no doubt that my mother is in a much better mood since Fourteenth’s visits to her; her very complaints about her sister have a gleeful quality to them.

As for me, whatever Fourteenth Aunt did for me, I wanted more. I dreamed of a toothless old woman with sunken lips at a flea market. She sold me a bicycle. Later I discovered it to be missing a handle. My jump rope handle didn’t work very well on the bike. So I went back to her, and she rummaged in her junk but found only some pictures of the revolution which we duly admired. She said she’d keep an eye out for a handle; meanwhile, ride on and be calm…

It was a couple of years after Fourteenth Aunt’s return to China before I found time to write about her trip. I named my piece Fourteenth Aunt’s Glorious and Pragmatic Visit to America. Although it was a true story, essentially the same as I have told here, I was dissatisfied with the ending. I felt the need for something with more punch, flashier, something that lived up to the title of the piece. I wanted to imbue Fourteenth with some act of heroism. On a rewrite I succumbed to a flight of fancy. This was how my piece ended:

“Early morning on one fall day in San Francisco CAAC’s flight to Beijing took off. In its belly sat Fourteenth Aunt, silver pellet under her tongue, eyes closed, seatbelt buckled. After the plane leveled a bit, she unzipped her flight bag, and fished out the end of a strand of gray nylon yarn, crinkled from a previous knit. She started winding it upon two fingers, and then slid the loop off and wound the rest upon itself with quick and easy strokes until it began to form a fine round ball, ready for reknit. As the old gray sweater inside her flight bag steadily dwindled, so did the continent of America beneath the giant flying machine.”

I went up to see my mother meaning to check some facts such as her mother’s cause of death and her father’s favorite gambling game without meaning to give away the true subversive use of this information. I had, of course, no intention of showing her my story, a story in which her Fourteenth Sister was the heroine, her daughter the heroine’s accomplice and herself, the ogress.

The next morning we were outside her house, and I was preparing to leave. As the fog gradually dissipated around us I noticed that she was wearing an unusual sweater. The light green yarn was textured and bumpy quite unlike what she usually bought from Payless. I reached over to feel it. “What kind of yarn is that?”She laughed at my interest. “I unraveled that awful sweater Fourteenth made for me and reknitted it!” Her tone was triumphant.

Stunned, I did not yet concede defeat. As soon as I got home, I rushed to the phone and punched the numbers in a flurry of hopeless hope. “Fourteenth Aunt, its Ah Tung, how are you?…I’m fine… my mother’s fine too…I want to ask you about that gray sweater your friend in New York gave you…yes…what happened to it?…Oh…it’s in your trunk? Oh… You didn’t unravel it, did you?…No?…Oh, nothing…never mind…I thought you might have unraveled it and reused the yarn…” No. She hadn’t.

About half a year later my mother told me that she’d received a letter from Fourteenth Aunt saying she had married again. Folded in it was a small black and white photo of her with her new husband, two old, weary, citizens of the People’s Republic of China. I looked hard at this tiny image of Fourteenth. Would I know her if I met her in a crowd?

After suffering several years from dementia my mother died. I wrote to Fourteeth Aunt. Sixteenth Uncle answered my letter. He wrote that Fourteenth Aunt was similarly afflicted and no longer able to care for herself. I have not yet written back.

My Mother Eating