A Penetrating Relationship

If you have a hole

You want to fill

A wall to plaster

Anything to coat

Against the rains

If you need fuel

To cook your meal

Look to cow dung.

From Karandih to Kampung

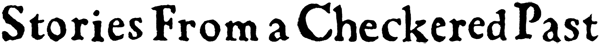

Barefoot kids with switches

Follow bony water buffaloes

Along narrow paths

Between rice paddies

Swatting mindlessly

With willow branches

At greenbacked flies

Swatting and waiting

For shit to fall.

Under an enormous full moon a line of dancers ringed the clearing , arms linked in a single snake like circle. In the center were several musicians: a couple of drummers, another with a bow like instrument that added a boingboing droning beat, a couple with flutes. The musicians and dancers challenged each other with increasing intensity. At the head of the line was an energetic young guy with a feather on his head and more feathers in one hand; he was followed by maybe twenty or so men and women while a straggle of kids of decreasing sizes brought up the rear. They broke into repetitive high-pitched chanting. My heart was pounding.

At the edge of the clearing a couple of conspicuous wood chairs had been set up. We sat down. Martin, my husband, was an anthropologist on a Ford Foundation grant to study the Santals, one of the very primitive aborigine tribes of India. I was with him to be his field assistant. This was my first introduction to the tribe—to any tribe. The name of the village was Karandih. The year was 1957.

A woman approached bearing a large brass tray upon her head. She removed the tray from her head and placed it on the ground in front of me. She squatted and, without further ado, pulled the sandals off of my feet. I stopped breathing. No one had prepared me for this. Placing both my feet upon the large tray, she poured cool water from a brass jug upon them. She gently washed my feet, and then anointed them with oil from a small brass bowl, massaging it deep into my skin. The oil had a very distinctive somewhat spicy smell.

My feet were still on the tray and I was about to remove them when she suddenly grabbed my ankles, and held them down. I yanked, first tentatively, then with more conviction so that my intention could not be misunderstood, but I failed to loosen her grip. I had no idea what this meant or what I was to do. Standing up, I tried, once more to tug on my feet, but she had them firmly trapped. I sat down again. What with the full moon, the intense drumming, falsetto chanting, circular dancing, and then the unexpected turn of the foot washing ceremony I was on the verge of a serious loss of anthropological cool. Visions of being eaten alive by cannibals, scenes from old Hollywood movies, were beginning to creep into my consciousness.

I shot a glance at Martin but, not only was he unconcerned, he was amused. I turned behind me and caught the eye of the man who had brought us here, a follower of Gandhi, but he too was chuckling at my obvious consternation.

“What should I do?” I asked him. He bobbled his head in typical non-committal Hindu fashion. “Please, tell me what to do.”

“She wants something from you,” he said with another annoying bobble.

“What?” I asked. “What does she want?”

“Give her a present,” he advised me. OK. A gift. What should I give her? I dug into my purse and wondered what sort of gift was called for here. Money? Too mercenary. It might offend. I sifted through the assortment of my belongings and settled on a small sewing kit in a little purse—the kind that opens by twisting two little round balls. I placed it on the tray. She eyed it but made no move to release me. A giggling, chattering crowd was beginning to form around us. I turned, once more, to the Gandhi follower.

“Rupees,” the man said. “Give her rupees.” Relieved, I dropped some coins with a clatter. She remained solidly unmoved. The man nodded at me. I dropped more coins onto her tray. The man said something to her and she seemed finally to be satisfied and let go.

As she rose into standing, she once more bent toward me and gestured toward my face with one hand. I started back, which occasioned another round of mirth. Grabbing the air near my lips with the tips of her fingers, she brought her hand back to her own puckered lips, and made a Santali version of an air kiss—a ceremonial blessing that I would see repeated many times in my time with the Santals.

“What did you say to her?” asked the anthropologist.

The Gandhi follower bobbled and smiled. “All the crab’s legs have fallen off.”

“What does that mean?”

“She has given all she has. All the crab’s legs have fallen off.”

We rented a place not far from Karandih. It was a mud house built on a small hill with no other house in sight. It was divided into quarters– four rooms, each led to the other and each opening out upon a veranda which ringed the house.

Our first morning in the house Martin and I struggled with the kerosene stove—the kind you pump to get started. There was a little tool with a thin wire at the end with which you were supposed to clean out some tiny air hole. Hours later, we were still struggling with it. No breakfast. Four year old Shima, was getting crankier and crankier. In fact we were all at wits end when a man, a woman, and two kids appeared at the bottom of the steps.

“Do you need help?” the man asked. Yes! Our summer spent in intensive training in Hindi at the Language Lab, stood us in good stead. Yes! We bobbled! Do you know how to work this? We hired the Muslim couple on the spot. He got the kerosene stove going in no time and cooked some eggs, potatoes and onions and totally saved the day. Yaseen, his wife, Sakina, and their two children Nasru, about eight, and Munee, a bit younger, moved in with us.

Attached to the rear of our house, on a lower level were two more adobe rooms. One was used by them for a bedroom, and the other, on the other side of some steps, was a primitive kitchen with a mud stove. Further from the house there was a well. That was it; that was all we needed.

We set up housekeeping. I quite enjoyed the whole process; there was something familiar about it, reminding me of when I was a refugee kid in China, being on the move, always a stranger, struggling with the dialect, facing new challenges. I was an old hand at this. Life was simple and good.

On the same day every week, an old man with a turban known as The Egg Walla came. Sakina would fill a bucket of water from the well, and we would crouch around his basket of eggs and them by lowering each one into the water. Good eggs sank readily to the bottom, floaters were rejected. The rest of our food was bought at the small local village markets; we were able to get fresh vegetables and rice and dal, oil, sugar, salt, spices. Occasionally a goat was killed and we got a piece of that. Sometime a villager would come to the house and sell us a chicken or two; once a woman came with a single egg. It sank; I bought it.

One day a herd of sheep came near the house. They left a baby sheep behind. Shima immediately adopted it.

Every morning Pradhan came to have tea with us and give us lessons in Santali. He was the young man who’d led the dancers in our first night in Karandih. Among the Santals everyone is related, and relationships dictate the nature of the interaction. As Pradhan undertook to be Martin’s little brother, I was his older brother’s wife. We had the prescribed teasing, joking, flirting relationship. No matter what you asked him, he bobbled. Not yes, not no, not I don’t know, or, perhaps, all of the above.

It was up to me now to get in with the women, Martin said, then roared off on his Jawa with Pradhan behind him. When I could dawdle no longer, I left Shima home with Sakina and headed down to Karandih on my bike to begin getting acquainted with Santali women.

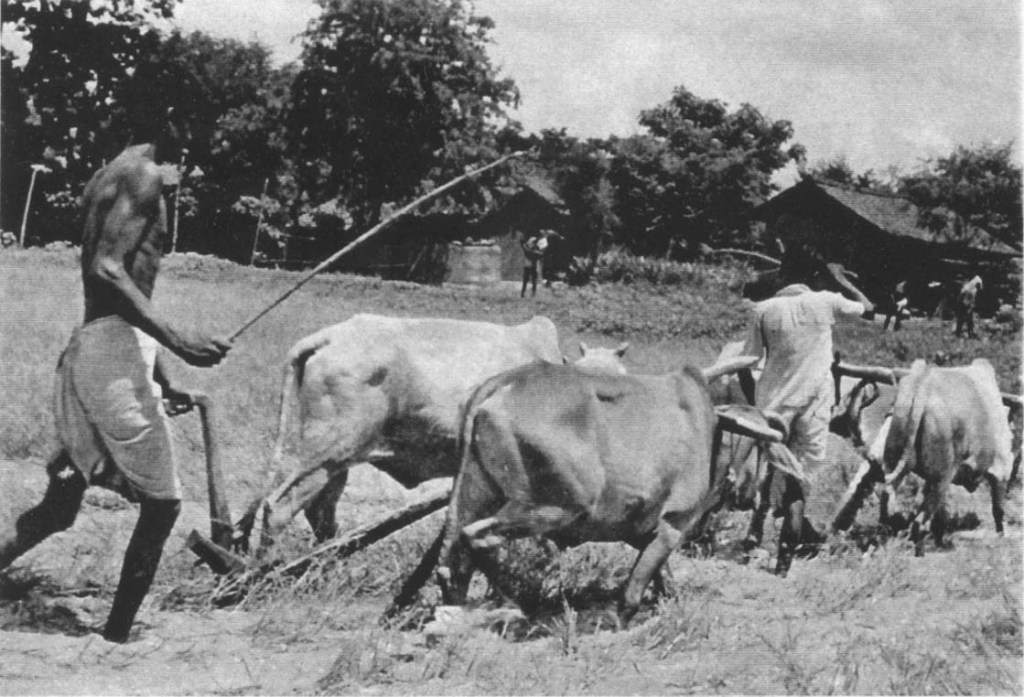

In my bag I carried a little notebook, a canteen of water, a camera and some candies for the kids. The clearing where the dancing had taken place some weeks ago was now empty except for several string cots. Kids had spotted me as I rode in and I gave them some candies. More kids came and I passed out more candies. I sat down on one of the string cots. Adults joined the throng of kids. I gave them candies.

They didn’t speak Hindi; I didn’t speak Santali. I nodded, I smiled, I made polite eye contact, I did the Namaste over and over, but nothing worked. Aside from a few uncomfortable giggles, they simply gawked and chatted among themselves. It was clear that in Santali culture there was no taboo against staring.

The next day was a repeat and the next. I can no longer recall how long the shut-out lasted. But the pain was unforgettable. Whose cot was I so rudely occupying day after day? Who invited me? Where could I hide? Thinking back, maybe there were other moves I could have made to get the kids engaged—like drawing pictures or something. But at the time the lack of any welcome had me completely stymied.

At one corner of the clearing lived a woman with a daughter about Shima’s age, and a boy a little older. Her name, I learned later, was Solma. One blessed day she came out of her house and gestured at me to come. How gratefully I pushed my bike over. She led me into her yard where she sat me down on her string cot.

We were surrounded by about a four-foot reed fence. Heads appeared over the top, gawking. She yelled at them. Some left. But then through the door came her cronies, among them an older woman with almost no teeth who knew a little Hindi. She asked me where I was from. I said “China” which drew a blank. I immediately regretted my answer. The Santals were an extremely primitive people, with no written language, barely emerged from hunting and gathering. What the hell was “China”?

In America I was used to explaining that it was on the other side of the globe, but here I was on the same side and dealing with very different natives—or perhaps not so different “It’s…uh…a country very far away,” I explained.

They talked amongst themselves giggling and I caught the Hindi words “bara memsahib.” That was not how I wanted to be known. I did not want to be identified as a high caste lady. In my stilted Hindi I said I am not a “bara memsahib.” Slowly I got it out. “My husband and I are students.”

Toothless, who seemed to be dominant in this small group of curious ladies, brought brass jugs of water and oil and bathed my feet on a large brass tray. It was marvelously cool and soothing.

My attitude toward foot washing had evolved. This was how Santalis welcomed those, who had, presumably, walked from distant places on dusty barefeet. Perhaps they thought I had walked from China. She massaged my feet with what I now recognized as mustard oil. Then she grabbed my ankles.

I clattered a bunch of coins on the tray with aplomb. Toothless let go quickly and finished with the prescribed air kiss in which she plucked the air near my lips and brought it to her own with a kiss.

“I come from a far distant land to learn the Santali way,” I said. I had read that they were very proud of “the Santali way”. They are a proud tribal minority embedded in a Hindu society that denigrated them and called them “junglis”, one step up from monkeys, lower, even, than the lowest caste, the Untouchables.

Toothless said, “To learn the Santali way you must do everything we do.”

“I will do everything you do,” I pledged. That was exactly what I wanted to do.

“Everything?” It sounded a bit like a dare.

“Everything.”

Heads, once more, had popped up and lined the top edge of the fence. The older woman gestured for me to follow her. She picked up a short broom with stiff bristles and headed for the big pile of cow dung rotting in the corner. She plunged her left hand into the shit and in the same movement plopped a wad of it onto the middle of the yard. With the broom, she spread the brown mixture in a smooth thin layer as if applying tar. She handed me the broom.

No high caste lady, no Hindu lady of any caste, no white lady, no Chinese lady, no lady of any shade whatever was likely to consider such a penetrating relationship with this mound of smelly, fly-specked, undoubtedly disease ridden cow dung. I could not afford to hesitate. Marching with determination toward the putrid dung pile, I plunged my left arm into the warm, stinky goo. It went in deeper than I had intended—almost up to my armpit. Without pause, I slung the shit toward the middle of the small yard and splattered a bunch of faces on top of the fence. A huge roar of laughter!

“Handi, handi, handi!” The cry for rice beer went up, and I was in.