In America at Twelve She is Propositioned by a Singing Cowboy

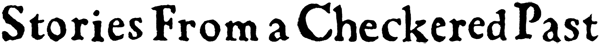

The SS George M Randall delivered us to San Pedro on March 1, 1945. After two months of being at sea, cramped into one large room below deck, along with countless women and children in three tiered bunks, eating scrambled powdered eggs, canned creamed spinach, and fruit cocktail in green lime jello that wobbled with the waves, I had written in my diary:

I am dying for some rice gruel, pickled mustard root, stir fries, and other small delicacies.

On most nights, children on the floor, grownups in folding chairs, we watched movies of our destination: gunslinging, ballad singing cowboys in high-heels galloped on splendid horses across vast arid landscapes; tree-lined streets where sunlight sparkled through leaves and dimpled Shirley Temple roller-skated past white picket fences; Spencer Tracy, the saintly priest battling the forces of evil…

We landed here in the last days of WWII. Along with the other Chinese refugees we stayed in a seedy waterfront hotel in San Pedro that smelled of moldy old carpeting. I remember clanging down the rickety elevator three times a day, walking to the corner hot dog stand, and each of us eating a hot dog and a Nehi orange soda, three times a day, the three of us, my mother, my brother and I. My mother’s English was good enough for reading the novel, “Rebecca” but not for ordering food. It was days before she was able to get us hot dogs without the unspeakably sour yellow squiggles.

Wartime regulation limited civilians to hotel stays of ten days or less. The next ten days we spent in San Francisco at the very posh Palace Hotel where, day and night, the brass was always being polished. In the high domed dining room with a glass ceiling my mother, unable to fathom the menu, ordered strange, inedible concoctions that we had to eat because we were afraid of the waiters who wore white gloves, and on top of that there was the agonizing dilemma of which silver fork or spoon to use for what dish.

Ten days later we took the train to Davis. We checked into the hotel right next to the train station upstairs from the Davis Cafe—The Davis Hotel. In those days UC Davis was a small agricultural college where my mother was planning to study.

My mother placed absolute faith in total immersion. My brother and I were sent to school immediately. I entered sixth grade using the English name “Marian”, given to me on the ship by my best friend, Betty, and my brother, named after Max of the novel, “Rebecca”, started in first.

Papers were being handed out. A . Multiple choices. The form was delightfully familiar to me if not the content. Never mind. I checked away with aplomb. The teacher, an extremely tall, skinny man with a nose the size of Everest, addressed me; I leapt up and stood at attention. This got a huge laugh from the class. They didn’t do that in America.

In tumbling class the stout woman teacher in tight blue shorts and even tighter flesh, flesh that clabbered on her thighs ordered me to do something. What I had no clue. She said the same words again only louder. I still didn’t get it. She repeated it the third time, then a fourth, louder and louder—with no better results. She got very angry and dragged me by one arm to stand in the corner.

Meanwhile some kids thrashed Max for the same offense—not understanding. It was quite peculiar that they did not understand not understanding. We picked up English super fast.

Across the street from the Davis Hotel was Lee’s Chinese Restaurant. The Youngs who had bought the restaurant from the Lees were the only other Chinese in Davis. Everyone directed us there. However, The Youngs were from Canton. We were from Beijing. We spoke different dialects and communicating was not easy. Actually in Kowloon where we had lived for almost a year we had to learn to speak Cantonese, but it was not the same variety of Cantonese that the Youngs spoke. Either they spoke sam yup and we spoke sai yup or vice versa, I can’t remember. But this was a common problem in China and the subject of many jokes, certainly not anything to be angry over.

One of the Young kids, Alice was in my class. There was to be a party at the restaurant: St. Patrick’s Day Dance. My invitation was printed on green paper.

I didn’t have anything like what Shirley Temple might have worn. We were still living out of a couple of suitcases and our breakfasts were eggs cooked over a can of Sterno in our hotel room. My mother said well, I should just wear the best clothes I had and all would be well: a skirt with suspenders tailored in Hong Kong out of heavy worsted British wool, grey with red pinstripes, a plain white blouse that had been part of my school uniform in Kowloon, thick cable-knit grey woolen knee socks, and heavy leather oxford shoes.

Clonkclonkclonk! All was not well. The girls were in pastels, taffetas, filmy chiffons, and shiny patent leather mary janes. They swirled and twirled in their ribbons and lace. They rustled their taffeta. They tossed their ruffles. They shook their curls. The boys wore suits with hair slicked back ever so neatly parted. They posed and postured and swiveled on stools at the counter. I died and was buried in high class British woolens.

Worst of all–I was voted the best-dressed girl. Then I had to dance with the best-dressed boy, Larry Turner, I’ll call him. Dance! By ourselves! In the middle of the circle. He was kind; he showed me how. But no amount of kind could possibly fix my agony.

After school one day a boy in a cowboy hat, beat up, high-heel pointy boots, Levi’s, and white T shirt came down the sidewalk where I stood waiting for the crossing guard’s signal.

Davis had tree-lined streets, white picket fences, and Davis had a real live cowboy. I’ll call him Rich.

“Hey,” Rich said. “How do you say I love you in Chinese?”

I sucked air and froze. A trap. If I said those words I would be bound to him for the rest of my life. A cowboy’s wife! I ran.

Three or four years later we were in Miss Ratzell’s Latin class. The little finger on Miss Ratzell’s right hand was bent as she wrote on the blackboard. After days and weeks of careful observation I’d decided that it was a permanent disability turned into a rather elegant habit. I admired her powers of transformation. She was not married and lived alone. Something about her reminded me of a nun, actually a particular nun, Miss Stevens of the USS George M. Randall, who had taught us to carve elephants out of ivory soap. One night coming out into the hallway outside of our lower deck sleeping quarters to get a drink of water, I had spotted a strange little man at the fountain. He had turned and given me a sweet smile. It was not until I returned to my bunk that I figured out it had been Miss Stephens without her habit and exposing a shaved head. Miss Ratzell and Miss Stephens, two mysterious women who lived without men.

As Miss Ratzell turned to the board to erase something, Rich, sitting behind me boots up on an empty desk, passed me a dark wad and pointed to a bulge in his cheek. I thought it was something like chewing gum, and popped it in my mouth. O no! It was as if I had swallowed fire. I had to run out of class to spit out the burning brown juice. Chewing tobacco! Another strange American culinary delight. Amo, amas, amat…

Junior year– he called me. “Uh…my folks are away for the weekend, ya wanna come over?” His voice had deepened into a throaty bass.

As I walked over to his house, passing the high school, passing Kozy Korner, the soda fountain, I was in a state of unbearable excitement. His house was an imposing two-story affair about four times as big as mine. His father was a dean in the college. Never mind that my father was the Foreign Minister of Taiwan; that counted for zilch in Davis. The sound of his trumpet wafted down the block.

I sat stiffly on his lap as he continued to blow his horn–no melody, no song, just the damn scales, then thirds, then fifths, interminably leading finally to grappling and groping with his free hand–a fifth of the way to my underpants, a third…. I jumped off his lap. He didn’t love me; he only wanted sex! He blocked my way to the door; he herded me toward the stairway. “Wait. Don’t go yet. Come on. Come on upstairs.” The coaxing voice, the intense blue eyes.

So what if he only wanted sex whatever that was? No one had ever wanted that from me before. Gold rodeo trophies dominated his room but there was no time to admire them. He wrestled me to bed; I kept my legs clenched. I knew what happened to girls who went all the way. They went the way of M. C. , one of the most popular girls in school who disappeared and was never ever seen again.

I hungered for romance, what I’d seen in movies, but he was only interested in penetration. The battle ended in my giving him a hand job into the toilet. It was about as romantic as milking a cow.

Yet we repeated the scene at various locations. Late at night he tossed gravel at my darkened window. I unlatched the screen, climbed out of my window and into his pick-up….

In school we avoided each other as we always had. I wrote a gossip column for The Hub, our high school paper, a la Louella Parsons . “What did R give to V under the bleachers at last Friday’s game, and does this make it official?” I practiced sounding like an “insider” when nothing was further from the truth. I got no dates, sat with girlfriends at all the hops, ate my heart out, and pretended not to care.

This ghastly period finally came to an end when I got a scholarship to the University of Chicago and left Davis for good, except for brief visits to my mother.

40 years passed. Marriage, 2 kids, divorce, sex, drugs, and rock and roll, an affair with a woman, Hong Kong, making documentaries for television, retirement, out of the city to Bodega Bay. I was in bed with my two dogs and one cat when the call came.

“You’re never gonna believe this, you’ll never guess who this is…Rich…”

We talked and talked. He called me several times a week. A talent scout had discovered him riding in a rodeo. He was taken to Hollywood where he became John Wayne’s stunt rider. All those shots of John Wayne doing just about anything special on a horse, it had been Rich.

We did not talk about our covert, adolescent affair, but I did tell him how miserable I had been in high school. He said he only got through with the help of booze. His father had started him when he was around four or five giving him a shot of whiskey to use as a gargle every morning as he himself tossed down a couple to start the day. He followed in his father’s footsteps; all the men in the family were drunk all the time. Why did I think he always wore cowboy boots? Hell of a good place to stick a damn flask.

“You were drunk all the time in high school?” Hell, yes every single day. He was so pickled not even cancer could get him.

I had to ask him pickled or not. “There is something that has bugged me all these years. I always suspected that you never took me out publicly because it was not OK to date across racial lines.”

“Hogwash! I never dated any girls; I didn’t know how to act with girls.” Well he hardly had to tell me that.

“What about that blond you took to the Jr. prom?”

“Her! Her dad let me graze my herd in his meadow. He asked me to ask her to the prom. What the hell was I to do?” As proof of his innocence he played me an audiotape of John Wayne on race. We oughtta just get rid of the dashes: Korean-American, African-American, Mexican-American…we’re all just plain Americans…

I was unimpressed. “Tell ya what,” he said. “Let’s go to the reunion together.”

“You got a date.”

About a week before the reunion his calls stopped. When I called him before I left Bodega Bay to tell him I could be there around four, he was strangely nervous. “Isn’t that too early? Dinner’s not till six thirty. Come at six.” Fishy, but maybe he just needed a drink.

By the time I’d driven through the huge college suburb that Davis had become I was haunted by so much adolescent angst that I was the one who needed a drink. No matter how far I had come, in Davis I would always be that twelve year old alien passenger who stepped off the ramp of the SS George Randall.

His house was only three blocks down from where he had lived with his parents where we had our first clandestine assignations. But his was much less of a house: a ticky-tacky cottage with aluminum windows. When he came to the door, before I could really take him in, I noticed the blond standing in the shadows behind him. He introduced her as his neighbor who was breaking up with her husband and was staying with him. He’d invited her to come with us.

I took it in the worst possible adolescent way. Blue-eyed cowboys, young blond sirens I breathed fire and fully planned to eat them alive. In the car I was ultra cheerful and needled Rich about how cool it was of him to take two dates to the reunion. He dropped both of us at the door of the hotel and said he’d meet us inside. I went quickly ahead alone and entered the double doors of the ballroom. It was filled with old white people! I thought I had walked into the wrong room, and instantly backed out, but the sign in front read: “Davis High School 40th & 41stYear Reunion”

We all wore name tags with our grammar school photos on them. Putting on my reading glasses I peered into the past. With the help of a few sips of wine, I began to recognize them. Gradually the masks of age peeled off. They were so much like they used to be. Even me! Making documentaries for television was not so far from the insiders’ column I wrote for the Hub.

Then the thing with Larry happened. During the banquet as we were arrayed around big long tables, someone was passing around a letter from Larry, my partner in that unforgettable St. Patrick’s Day dance, my best friend in High School. He was mentally ill and living in the VA Hospital in LA. They were reading it aloud.

He had written me a similar letter—about having found his “real” parents: Fred Astaire and Mabel Norman. They were laughing. I was not.

From the other side of the room came another voice. It was Lillian, one of the organizers of the reunion, in the take charge tone of a grade school teacher putting down some unruly rascals, “That’s enough. Give me the letter.”

But apparently that wasn’t enough. Later C. and R. and Rich were standing around swapping stories. They got to reminiscing and laughing about what they did to Larry one winter night. They had driven him out into the country, stripped him of all his clothes, and left him there to walk home naked through the bare fields.

That was all that I could take. I piped up. “That was awful! Small wonder that he turned out the way that he did!” What else had they done to Larry? I walked away.

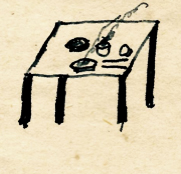

I did not see Rich again until he appeared for a photo opp, grabbing me in one arm and Alice in the other—his two Chinese. Smile! Then he took the stage and did his cattle auction thing with high school memorabilia for charity. Then it was over.

At his house we were finally alone. He offered me a drink which I turned down, but I was still looking for something even though the dream of a Hollywood ending was well demolished. Maybe some sense of symmetry.

He limped around showing me his house. Every bone in his body had been broken from rodeo riding and he was plagued by arthritis. His living room had knotty pine paneling decorated with antlers of deer he had killed. His bedroom had a huge King sized waterbed and even more of the same kind of rodeo trophies he had won in his youth.

Outside in his yard behind a chain-linked fence he had a couple of hungry hounds he said he was starving this month in preparation for the deer season. Hungry hounds made better hunters, he said. They didn’t look too friendly.

A horrible memory surfaced. I had a new Springer Spaniel puppy, my first dog in this country. I took it over to the Wilsons, friends of my mother’s. In back of their house they had a chain linked pen of hunting hounds. I let myself into the enclosure thinking the dogs would befriend my puppy. One of the hounds grabbed him from my arms, gave one quick shake and instantly broke the puppy’s spine. It died writhing on the Wilson’s kitchen linoleum floor.

Rich stood by his pick-up. “I know you’re not going to believe this, but I have to tell ya. I have always loved you. From the first time I saw ya. I mean it.”

There it was. “I have always loved you.” The words I had so died to hear forty some years ago. And I even believed him.

But… a boozy, decrepit cowboy’s wife?

“I gotta go, Rich,” I said softly and turned away.